PhD Reset: Start your Semester off Right

There’s something exciting about academic research, isn’t there? Sure, there’s loads of work to slog through. But at the end of the day, your job is basically to answer tough, interesting questions that will reveal new knowledge and hopefully make our world a better place.

It’s a pretty awesome job description!

Unfortunately, the work doesn’t always feel so impactful. As we roam from semester to semester, it’s all too easy to lift our heads up after weeks of data cataloging, experiment troubleshooting, or code debugging to wonder whether these mundane tasks will really help us accomplish our research vision.

Will the tasks you work on each day fulfill your research motivations?

Will they further your dissertation so you can defend your work and graduate?

I want you to be able to answer both of those questions with a confident, “Yes!”

That’s the goal of this PhD Reset.

To accomplish that goal, we’ll work through four different sections where we’ll discuss some amusingly thoughtful anecdotes, I’ll ask a series of probing questions, and you’ll do your best to answer them. Sounds like fun, right?

To get the most out of this time together, I recommend that you:

Write your answers down. Bonus points for writing in a notebook—there’s something psychologically powerful about connecting your thoughts through the movement of a pen to a physical piece of paper.

Take breaks between sections. Give yourself 15-30 minutes to go on a short walk and mull things over. Let your brain consider what you’ve written until you’re ready to move on to a new topic.

Work somewhere stimulating. No, that doesn’t include your sterile laboratory or your windowless grad school office. Sit under that ancient oak tree across campus, visit that hallowed library that won’t let you bring any food or drink inside, patronize that rooftop coffee bar you never seem to find time for, and enjoy a day of setting your semester on the right track.

So, go find that special somewhere and let’s get started!

Section 1. Your Priority Project

Think back to the last time you felt excited about research. Maybe that was after completing a recent milestone or even back to when you wrote your grad school application. What problems were you excited to solve? What knowledge were you curious to discover?

The way you answer these questions reveals your personal research motivations. These motivations drive your enthusiasm for work. They strengthen you with the belief that your research matters. If you complete projects in line with those motivations, then you’ll find work more satisfying, which will reinforce your motivations and create a virtuous cycle.

The problem is that universities are bustling places with many distracting opportunities. It’s easy to wander down a fruitless research tangent, accept interesting extracurricular responsibilities, or sink extra effort into a service role. None of things are bad. In fact, they’re a great use of your time. But if they stall your research progress by distracting you from completing a priority project…well that’s just disappointing isn’t it?

“Wait, what do you mean by a priority project?” I’m glad you asked. Your priority project is the most important thing you’re working on this semester. It’s a pivotal achievement—finishing an experiment, drafting a journal article, presenting a research proposal—it’s the one thing that you must accomplish to call this semester a success.

Your priority project is also the topic of this section of the PhD Reset: it’s the thing you’re going to identify in the writing prompts below.

But before we get to that writing, let’s discuss a bit of academic goal setting theory.

I’m going to make an assumption about your long-term goals: you want to look back many years from now and realize that your scattered accomplishments did little to satisfy your personal research motivations. No wait… that’s the outcome you’re trying to avoid! You want to look back many years from now and see a consistently growing body of work that answers important questions aligned with your research motivations.

It’s a nice dream. But it’s too abstract: personal research motivations, a body of research work—these are nebulous visions that unfold over many years. You need to focus this abstract objective towards a scope and time horizon that are easier to envision.

So, let’s make things a bit more concrete.

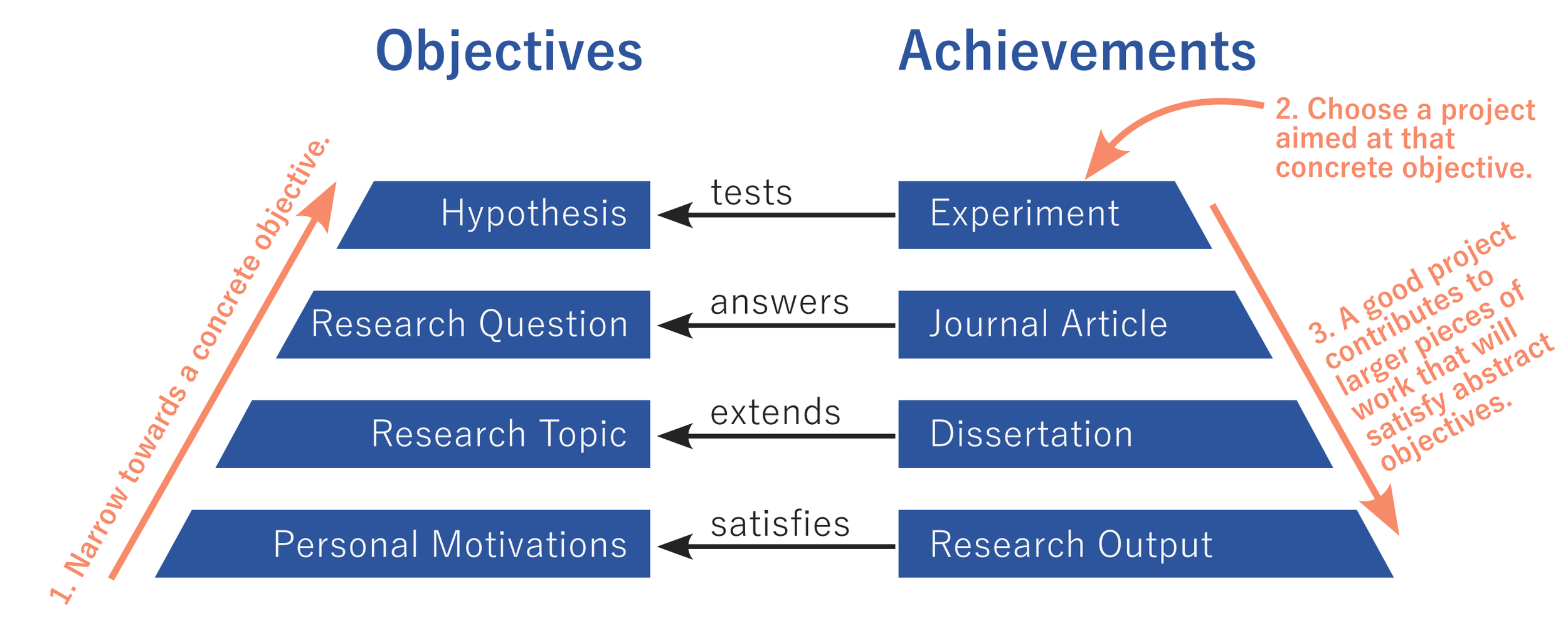

Consider the chart below. When we plan our day-to-day work, we need to operate at the top of this pyramid: we need a concrete objective—like testing a hypothesis—that can be satisfied with a distinct project—like running an experiment. This scope is easier to wrap our brains around. But we also need to ensure that that project contributes to larger pieces of work—like a dissertation—and fulfills more fundamental objectives—like exploring a research topic.

Fig 1. Narrow your objectives from abstract to concrete. Choose projects that will fulfill those concrete objectives.

To accomplish that, we must 1) narrow our abstract motivations towards concrete research objective and 2) choose a project that will satisfy that concrete research objective. In your case, this semester, you want to finish a priority project that contributes to a journal article, conference presentation, or other piece of work that ultimately advances your dissertation. And you want that project to help you answer a research question that adds new knowledge to your research topic area. The more projects like this you finish, the more you’ll build a larger body of work that ultimately satisfies your long-term research motivations.

With that in mind, it’s time to identify your priority project for this semester. We’ll start with your abstract motivations so you can identify the drivers behind your work. Then we’ll narrow your vision from abstract to concrete as you home in on a project that you can achieve this semester.

Consider the prompts below. Write as much as you want in response. Don’t worry about grammar or coherence, just get your thoughts onto the page.

Writing Prompts

What interests you about your research? What attracted you to research in the first place? What knowledge are you curious to discover? How do you want your work to impact society?

What research topic are you exploring? What types of problems does your research field try to solve? What is known and unknown about your research topic? How does your research topic align with your personal research interests and motivations?

What research question are you currently trying to answer? What knowledge boundaries do you want to expand? What breakthroughs do you want to make? What unknowns do you hope to answer? How will answering your research question help you advance your research topic?

What is your next step in answering that research question? Do you need to test your hypothesis with an experiment, synthesize your research findings, write a conference paper, etc? Be specific and describe a project you can complete this semester to help you answer your research question. This is your priority project.

How will completing that priority project advance your dissertation?

Once you’re satisfied with your answers, it’s time to take a break and move on to the next section when you’re ready. I give you permission to enjoy a long walk to your local coffee shop first—you deserve it.

Section 2. Milestones and Rhythms

In the last section you identified a priority project that you want to complete this semester. That’s a great target to aim for, but the scope is still too abstract. When your target is many months out, it’s difficult to know whether you’re on track: whether the things you’re doing today will help you complete that project by the end of the semester. We need to break up the timeline from a single semester-long project to a handful of week-long tasks.

To accomplish that, you’ll need to dissect your priority project into a few milestones. In this section of the PhD Reset, we’ll organize your project into an outline and set aside time to work on it.

“The problem is,” you say, “I’ve made project outlines before, but they don’t work.”

Well, let’s discuss two reasons that your outline might fail.

Reason One: your plan is too inflexible; too set-in-stone.

Imagine you’re on a wilderness hike. Your goal is to set up camp tonight at a safe, scenic location. You have a destination in mind, and a few waypoints to hit along the way, but there are no manmade trails, so you can’t know the exact route you’ll take. Instead, you’ll regularly stop to consult your map, check if you’re heading in the right direction, and plan your next few hundred meters of progress.

Fig 2. Plan a few milestones rather than a detailed step-by-step outline.

In the same way, a good research plan has a few milestones that keep your project on track. But you only plan the smaller details for one milestone at a time. This type of plan is detailed enough to keep you from dabbling in tasks unrelated to your priority project, but vague enough that you won’t feel constricted or unproductive.

Reason Two: you lack rhythms for checking in with your plan and getting the work done.

Tell me if this pattern sounds familiar: you make a new plan for the semester, you ride that momentum for a few weeks and get a lot done, but after a month your progress feels stalled.

Why does this happen?

Even with a good plan, it’s difficult to remember your milestones and convert them into meaningful daily tasks unless you regularly consult that plan and implement it. Like our wilderness hike, you need to stop regularly, consult your map, and prioritize tasks that will help you achieve the next milestone.

Practically, this involves a weekly check-in and some daily workload.

A weekly check-in gives you time to 1) review your plan and your next milestones, 2) adjust any milestones as needed, and 3) choose some tasks to focus on next week. This check-in takes only half an hour, but it’s vital to staying on track. Choose a day and time where you can consistently do this check-in—I’d suggest Monday morning or Friday afternoon—and put a recurring weekly block on your calendar.

Daily workload means that you will make some slow and steady progress every day. Two hours a day, five days a week. Ideally the same time each day. Ideally the same place each day.

Must you work on your project daily? Ideally yes, because it’s easier to establish a daily rhythm than a sporadic rhythm like two or three days a week. And it’s easier for other people to manage their expectations of when you’re unavailable.

Okay, that was a lot to cover! It’s time to work through some of these ideas by engaging with the prompts below. Write as much as you want in response. Don’t worry about grammar or coherence, just get your thoughts onto the page.

Writing Prompts

What tasks do you need to accomplish to complete your semester project? Write down any tasks that come to mind. Don’t worry about whether the task seems irrelevant, too small, or too vague—write down everything that comes to mind. Stop when you run out of ideas.

What milestones will you accomplish on the way to completing your semester project? Take your list of tasks from the previous question and cluster those tasks into a few groups.

Group together tasks that require similar skillsets, contribute to finishing the same document or artifact, happen early or late in the project timeline, etc.

For any tasks that are difficult to group, you must either 1) delete that task from your list because it’s unnecessary, or 2) put this task as its own group.

Each group represents a milestone. Give each milestone a name. Put the milestones in chronological order or in the order you’d like to work on them.

When will you do your weekly check-in? Choose a recurring day—I recommend Monday morning or Friday afternoon—and put it on your calendar.

What will you do during your weekly check-in? Write yourself a check-list of things you must do during your check-in. At a minimum, you should review your priority project and milestones, make any adjustments as needed, and choose the tasks you will work on next week. Are there any other projects or responsibilities that you need to check on weekly? If so, add them to your weekly check-in—there’s no need to limit the weekly check-in to just your priority project.

When will you work on your priority project? Carve out ten-hours a week to work on your project. It’s best if you can do this two-hours a day, every day, at the same time, in the same place (in that order of importance). Of course, your schedule may not allow that. In that case, do your best to find ten hours during times and days that you can repeat from week to week. Find your ten hours and put them on your calendar. Treat these like recurring meetings that cannot be rescheduled.

Great work! Now take a short break before moving on to the next section.

Section 3. Habits

In the previous section, we identified a set of priority project milestones and carved out time for you to work on them during a recurring weekly and daily schedule. This is a great plan, and it’s going to work!

Unless, of course, you don’t keep to the schedule.

When we try to revamp our schedule, it requires us to change the way we do things. But we don’t like change. We are creatures of habit, and we want to keep it that way.

See, our actions rely on habitual, subconscious choices more than we’d like to admit. Consider how many things you do in the morning—shower, brush teeth, get dressed, commute to work—without actively thinking about any of it. Your brain is on subconscious autopilot. This is wonderful, because life has enough decisions without having to actively choose which leg to put into our pants first. But habits can also cause frustration when they don’t align with a new schedule. This misalignment creates friction, and that friction is harder to overcome than we might think.

The good news is that we can re-work our habits to align with our schedule rather than fight against it. In this section of the PhD Reset, we’ll build some good habits and break some bad ones to accomplish just that.

But first, a bit of habit theory.

Simply put, a habit is a reinforcing cycle. It starts with a trigger that causes a craving which leads to a response that ends in a reward. If the reward is a good one, our brain wants to do that habit cycle again. And the more habit cycles we complete, the stronger that habit becomes.

Fig 3. A habit is a reinforcing cycle.

Using that basic framework:

You can break bad habits. I’ve written a whole article on this, and the easiest ways to break a habit are to 1) identify the trigger of a bad habit and avoid it, 2) make it difficult to respond to the craving, or 3) somehow worsen the reward. For example, let’s say you have a bad habit triggered by boredom where you crave entertainment, pick up your phone, and are rewarded with a dopamine hit from your favorite social media platform. To break this habit, you probably can’t avoid boredom, but you could put your in another room to make it more difficult to respond, or you could set a time limit on your social media app that cuts it off after a short time and worsens the reward.

You can build good habits. You can design the trigger, response, and reward from scratch. Or, you can take an existing good habit and turn its reward into a trigger that sets off another habit you’re trying to build. For example, you might design a weekly alarm to trigger your craving for a pour-over coffee after which you walk to the nearby coffee shop and reward yourself with a beverage. That’s a pretty neutral habit, but you can use that beverage as a trigger to sit down and work on your weekly check-in after which you reward yourself with some music and a slow bike ride home.

Through this kind of strategic thinking, you can redesign your habits to support your weekly and daily recurring schedule. It takes some initial willpower to get these habits going, but once they’re established, you’ll start doing your weekly check-in and daily workload almost automatically.

In the questions below, you’ll identify some opportunities to use an existing good habit to support your work plan, identify a bad habit to break, and develop a new habit for your weekly check-in. Resist the urge to go overboard here by trying dozens of habit adjustments at once. Remember that your brain doesn’t like change, so it’s best to take these things slowly. Do this assessment each semester and before long you’ll have a slew of new habits to enjoy.

Now, work through the questions below. Again, write as much as you want in response and don’t worry about the grammar, just get your thoughts onto the page.

Writing Prompts

Think back to your daily work rhythms last semester. What were some of your best work habits? Describe those habits in terms of trigger, craving, response, reward.

How can one of those good habits help you accomplish the ten-hour work plan you described in the last section? Can you use an existing good habit’s reward to trigger a new habit that leads you to begin your daily work schedule? If not, what habit can you design from scratch to get you to the right place at the right time to begin your work plan? What trigger, response, and reward can you use to build this new habit?

During the last semester, what were some of your bad habits that made it difficult to get research work done? Describe those habits in terms of trigger, craving, response, reward.

Which of those habits is the worst one at slowing down your work progress? How can you avoid its trigger, add friction to your response, or worsen the reward?

Consider your weekly check-in schedule. What new habit can you design to get you to the right place at the right time to begin your weekly check-in? What trigger, response, and reward can you use to build this new habit?

Before you finish this section, take some actions to jumpstart these habit adjustments. Print out a list of these habit changes and post it above your desk as a reminder. Set up any alarms, apps, or other tools needed to trigger, block, or reward as needed.

Almost done! The last section’s a short one—I promise. Still, take a break and come back when you’re ready for more.

Section 4. Synthesize

Great work! You’re nearly done with your Semester Reset.

You reconnected with your research motivations, used them to choose a priority project for this semester, outlined that project into a few main milestones, scheduled weekly and daily rhythms to help you complete those milestones, and designed some new habits to keep those new rhythms going.

In this section of the PhD Reset, you’ll simply summarize that work. In this summary, you’ll pull those various ideas into a tight, cohesive vision that you can reference during your weekly check-in.

In the previous sections I encouraged you to write as much as you wanted to. But, in this section you should aim for brevity. Answer the questions as succinctly as possible. Trim it down to a single page that you can easily reference.

Writing Prompts

What are your main research motivations?

How does your research topic align with those motivations?

What is your priority project this semester?

How does that priority project contribute to your research topic and dissertation?

What are the major milestones for completing your priority project?

During which days and times will you work to complete those milestones?

What habit (trigger, craving, response, reward) will you use to keep that daily routine going?

What bad habit will you break to help you stay focused on your work?

How will you break that habit?

When will you do your weekly check-in?

What habit (trigger, craving, response, reward) will you use keep that weekly routine going?

That’s it! You’re done!

Well, one last thing before you’re totally done:

Schedule next semester’s PhD Reset. Aim for a Monday or Friday during the first week of next semester: look at your academic calendar now, schedule a block of time on the calendar now, and include a link to this page.

Okay, one more thing:

If you thought this helpful, please leave a comment and share with a friend. If you have any feedback, please comment or email me. This is an ongoing project and I’d like to improve it each semester. Thanks for your help!

Good luck! Let me know how it’s going!

-Thomas